Photo: Viola hastata, Tom Ward

In the Mid Atlantic region violets can be found in most habitats, from the dry shale barrens of the Appalachians to the marshy areas of the coastal plain. The yellow violets are typically found growing in moist soils often along stream banks and river plains. Bloom time depends on location, but it can be safely said that from late March into mid May is the time to keep your eyes peeled for these beautiful flowers.

Viola rotundifolia (Round-leaved Yellow Violet)

Photo: Viola rotundifolia, Blue Ridge Kitties

Viola rotundifolia is one of the most common and the smallest of our of the yellow violets. This is the only yellow violet in the east where the flower and the leaves grow on separate stems. In botanical terms this is referred to as the flower being unstemmed or acaulescent.

Photo: Viola rotundifolia, Blue Ridge Kitties

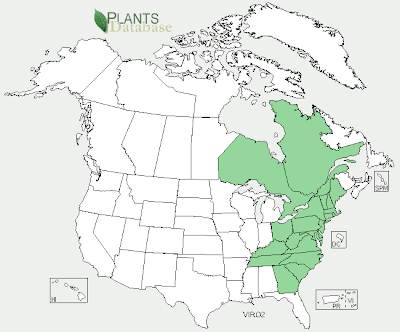

The range of the Round-leaved Violet in the United States is from Maine south into Pennsylavania and New Jersey. South of PA and NJ the plant is typically restricted to the Appalachian Mountains with scattered populations reaching into the piedmont. In the Mid Atlantic region there a only a few populations that touch the coastal plain north of the Mason-Dixon line.

Map of Viola rotundifolia, USDA Plant Database

Identification of the Round-leaved Yellow Violet is very easy. As stated above, this is the only unstemmed yellow violet in the east. This, along with the small size and rounded leaves makes for an easy id.

Photo: Viola routndifolia, Jason Hollinger

Viola pubescens (Downy Yellow Violet/Smooth-leaved Yellow Violet)

Photo: Viola pubescens, Pearl Pirie

The Downy Yellow Violet is another common yellow violet that grows throughout the Mid Atlantic region. The current taxonomy of Viola pubescens is somewhat muddy. Viola pensylvanica used to be a species called Smooth-leaved Yellow Violet. These plants were discovered to produced hybrids with Viola pubescens when there were populations of both species present in the same area. This hybridization caused some concern over the validity of the Viola pensylvanica, which resulted in the species being lumped into Viola pubescens. The end result is that there are two varieties of Viola pubescens: Viola pubescens var. pubescens and Viola pubescens var. scabriuscula. Fortunately, it is not difficult to tell the two varieties apart and it is still very easy to differentiate either of Viola pubescens varieties from all the other yellow violet species in our region.

Photo: Viola pubescens var. pubescens, Nicholas T.

Viola pubescens var. pubescens can be identified by the hairiness of the plant's stem and leaves. Unlike the Round-leaved Yellow Violet, Viola pubescens is stemmed, meaning that the leaves and flower share the same stem. Along with being hairy, the leaves of the Downy Yellow Violet are heart-shaped or cordate. The photograph below is an example of a cordate shaped leaf.

Photo: cordate shaped leaf, Zen Sutherland

Viola pubescens var. scariuscula is virtually identical to Viola pubescens var. pubescens except that the top of the leaves of var. scariuscula are not hairy but smooth.

Photo: Viola pubescens var. scariuscula, Dan Mullen

This is the only yellow violet in our area that regularly grows on the coastal plain. It is found throughout all the states of our region except the coastal plain of North Carolina and the southern portion of the Delmarva Peninsula. Below are two maps from the USDA Plant Database that show the state ranges of the two varieties of Viola pubescens.

Map of Viola pubescens var. pubescens, USDA Plant Database

Map of Viola pubescens var. scariuscula, USDA Plant Database

Viola hastata (Halberd-leaved Violet)

Photo: Viola hastata, Jason Hollinger

Viola hastata is not as common as the previous two species. This stemmed yellow violet is easily recognized by it halberd shaped leaves.

Photo: Viola hastata, SWG101

While the leaves are still considered cordate, they are much longer and pointer than the previously mentioned violets. The leaves of Viola hastata can also have silvery mottling like in the above photo. The yellow flowers of the Halberd-leaved Violet usually have a purplish wash to the back of the top petals.

Photo: Viola hastata, Jason Hollinger

Viola hastata is almost completely restricted to the Appalachian Mountains except in northwestern Pennsylvania and southwestern New York and it also grows in the piedmont of North Carolina.

Map of Viola hastata, USDA Plant Database

Viola tripartita (Three-parted Violet)

The Three-parted Violet is the rarest of the Mid Atlantic regions four species of yellow violets. One of the reasons for the plants rarity might be because it is difficult to identify because of the variability of the plants leaves. I could only get one photo of Viola tripartita to use in the blog, so I am going to give links to various websites to help give examples of the plants structure.

Photo: Viola tripartita, William Tanneberger

Viola tripartita at first glance closely resembles Viola hastata. There is one major difference between the two species. Viola hastata's leaves are always cordate, while Viola tripartita's leaves are always cuneate (wedge-shaped). On the website Alabama Plants, there is a photo showing the cuneate leaves of the Three-parted Violet. It can be seen here ALABAMA PLANTS. So if you find a yellow violet with halberd shaped leaves make sure you check tthe base of a leaf to see if the leaf is cuneate or cordate. This will give you the correct identity of the flower. Another website that gives more information on this species is Native and Naturalized Plants of the Carolinas & Georgia. There are more photos and some more technical info on Viola tripartita. It can be viewed here Plants of the Carolinas & Georgia. There seems to be two varieties of Viola tripartita, although there seems to be no consensus among botanists. The two varieties are separated by leaf structure. Viola tripartita var. glaberrima has cuneate leaves like we have discussed above and seems to be the more common variety in the Mid Atlatnic region. Viola tripartita var. tripartita has deeply divided leaves typically in three lobes. Var. tripartita seems to be the less common of the two varieties. More information and a photo of the leaves of Viola tripartita var. tripartita can be viewed at the website Wildflowers of the United States. It can be viewed here Wildflowers of the United States.

Map of Viola tripartita, USDA Plant Database

Viola tripartita seems to be extremely local throughout its range and seems to become increasingly rare in the northern portions of its range. In the Mid Atlantic it is found exclusively in Appalachian Mountains except for populations that grow in the piedmont of North Carolina. Since the above map has been published the plant has been found in Virginia and has become extirpated in Pennsylvania.

I would like to thank all the photographers who made this post possible, especially William Tanneberger who supplied the only only photo of the Three-parted Violet. Please go and check out their photo sites.

William Tanneberger -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/tanneberger/

Jason Hollinger -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/7147684@N03/

Dan Mullen -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/8583446@N05/

Zen Sutherland -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/zen/

Nicholas T. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/nicholas_t/

Pearl Pirie -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/pearlpirie/

Blue Ridge Kitties -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/blueridgekitties/

Tom Ward -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/taroman/

Maps were provided by the USDA Plant Database -- http://plants.usda.gov/java/

County level maps are available for all species at the Biota of North America -- http://www.bonap.org/

There doesn't seem to be any books that have been published in the past 20 tears that are exclusive to the wild violets of North America. If anyone knows of any books that I might have overlooked please let us know by putting the title and brief description in the comments section.