Vernal pools are teaming with life now that winter rains and snow have filled them with water.

Photo: Linda Ruth

These low areas that usually hold water from winter through early summer are very important ecosystems because this habitat allows certain frogs and salamanders to lay their eggs without the fear of their offspring being devoured by fish. Vernal pools also are the main breeding ground for many insects and fairy shrimp.

Photo: Fairy Shrimp by Linda Ruth

These animals are the main diet of amphibian larva. Many of these frogs and salamanders lay their eggs in mass. I am going to give information on how to identify amphibian egg masses that can be observed from winter into early spring.

First of all, it is important to be able to differentiate between a frog egg mass and a salamander egg mass.

Photo: Salamander egg mass by Richard Bonnett

In the above photo you can see that these eggs have an outer layer of gelatinous material that encapsulates the egg mass. All salamander egg masses in vernal pools will have this outer layer of material.

Photo: Frog egg mass by Ronnie Puckett

Frog egg masses do not have that outer protective layer like salamanders. The outer edge of the mass is made by the eggs. Once you have determined whether the eggs are from salamanders or frogs you can start to try to get the eggs to species. I have included maps from the USGS National Amphibian Atlas that show ranges for each species to county level. The color codes are as follows: Dark Green = Museum record, Middle Green = Published record, Light Green = Presumed presence, no green = no known occurrence.

Wood Frog

Photo: Bill Hubick

Wood Frogs are our earliest anuran breeder. They are very common in most wooded vernal pools. Wood Frogs are found in every state in the Mid Atlantic region.

Egg masses of Wood Frogs will have anywhere from 500 to 2000 eggs and the mass is very cohesive, meaning that the egg mass structure will hold together when taken out of the water.

Photo: Richard Bonnett

Individual eggs, when young, will have a black and white coloration. The white coloring will slowly disappear as the larvae mature. In the above photo the middle eggs are the youngest while the egg mass on the left is the oldest. After the egg mass has been in the water for a few days the distance between the embryo and the edge of the egg starts to expand. You can age a Wood Frog egg mass by how large the distance is between the embryo and the outside of the egg.

Northern/Southern Leopard Frogs

Photo: Southern Leopard Frog by Jim Brighton

Photo: Northern Leopard Frog by Jim Brighton

Leopard Frog eggs are easy to tell apart from Wood Frog eggs by the size of the egg and embryo.

Photo: USGS Amphibian Site

In a Leopard Frog egg mass there is usually twice as many eggs than in a Wood Frog egg mass, but the two species egg mass sizes are virtually the same. This means that a Leopard Frog egg is about twice as small as a Wood Frog egg. Their egg masses appear almost pure black because there isn't as much room between the embryo and the outside of the egg. Young eggs are the same color as Wood Frog eggs, black and white. Even though you can't tell by the above photo, Leopard Frog egg masses are not cohesive, meaning they will easily fall apart when taken out of the water. Often Leopard Frog eggs will be lower in the water than those of Wood Frogs. The eggs sometimes rest on the bottom of the vernal pools which means that the egg mass is often covered in silt and debris. Fortunately, Northern and Southern Leopard Frog ranges do not overlap that often, so getting your egg mass to species shouldn't be that difficult.

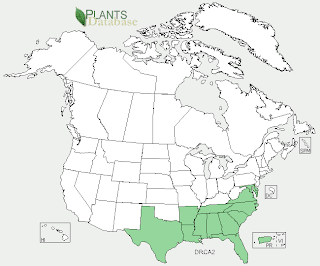

Northern Leopard Frog

Southern Leopard Frog

Pickerel Frog

Photo: Jim Brighton

The egg mass of a Pickerel Frog is virtually identical to Leopard Frog eggs. Luckily for us there is one characteristic that saves us from lumping Pickerel Frog egg masses in with Leopard Frogs. The eggs of Pickerel Frogs are brown and yellow not black and white. Unfortunately, I do not have a photo to show the noticeable contrast in colors. There is a nice photograph on the Virginia Herp Atlas webpage that shows the brown coloration of the egg mass. It can be viewed here:

http://www.virginiaherpetologicalsociety.com/amphibians/frogsandtoads/pickerel-frog/pickerel_frog.htm

American Toad

Photo: Jim Brighton

American Toad egg masses are the easiest of the anuran vernal pool breeders to identify. They are the only early spring amphibian breeders who lay their eggs in long strings. The egg mass often sits on the floor of the vernal pool resulting in the egg mass being covered in silt.

Photo: Rob Kirkland

Photo: Rob Kirkland

Southern Toad

Photo: Hunter Desportes

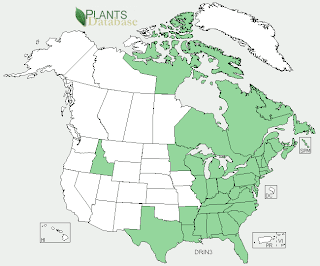

Southern Toads only hit the Mid Atlantic region in the coastal plain of Virginia and North Carolina.

Like the American Toad, Southern Toads lay their eggs in long strings. I couldn't find much information on Southern Toad egg masses but the eggs and egg strings are usually smaller than American Toads.

Photo: USGS Amphibian Site

From photos, like the one above it seems that Southern Toads egg strings lay straighter than the curly strings of the American Toad, but this is just my observation from looking at photos and may not be accurate. Luckily, the ranges of the two species only overlap in a few areas so it shouldn't be to difficult to figure out.

There are a few more frog species whose ranges reach into North Carolina like the Crawfish Frog and various species of Chorus Frogs who also use vernal pools for reproduction. Chorus Frogs normally have very small loose egg masses of between 10 to 50 eggs. Crawfish Frog egg masses closely resemble Leopard Frog egg masses, but you'll only have to deal with separating these species in southern North Carolina. Spring Peepers also use vernal pools throughout the Mid Atlantic region during the late winter and early spring but they normally lay their eggs singularly and not in large masses.

Most of the above photos were used under the Flickr Creative Commons license. I would like to thank all the photographers who made this post possible. Please visit their websites and peruse their wonderful photos.

Bill Hubick: www.billhubick.com

Linda Ruth: www.flickr.com

Richard Bonnett: www.flickr.com

Ronnie Puckett: www.flickr.com

Rob and Jane Kirkland: www.flickr.com

Hunter Desportes: www.flickr.com

The range maps I used are found on the USGS National Amphibian Atlas website.

These are the books I used when doing my research.

White, James & Amy. Amphibians and Reptiles of Delmarva. Centerville: Tidewater Publishers, 2002.

Conant & Collins. Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern/Central North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Martof, Palmer, Bailey, Harrison. Amphibians & Reptiles of the Carolinas & Virginia. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

Petranka, James. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1998.

Amphibiaweb is an amazing website. Hours of fun exploration available!

On the USGS website there is a page that has a field key to amphibian eggs of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Luckily, the Mid Atlantic region shares many of the same species. The key is really easy to use.

On Field Herp Forum there was a post that helped me greatly with this blog post. The photos are awesome and his egg mass descriptions are very clear and concise.